I didn’t know black bears lived in Los Angeles County until one shut down my high school for the afternoon. I remember the day well– our typically quiet English class was interrupted by the wailing of a lockdown alarm, followed by a loudspeaker blaring instructions to get inside and lock the doors. Our class formed a single-file line and marched down to join a group of other students and staff in the gym. Nobody seemed to know why we were in lockdown.

After several tense minutes, school security told us that the lockdown was caused by a wild black bear that had wandered over from the nearby San Gabriel mountains. The news was met with a mix of surprise and relief. Very few of us had seen a bear before. After all, our school was next to a freeway with a daily traffic volume of more than 100,000 cars. Were we really in bear territory?

The forested slopes of San Gorgonio Mountain, rising up to 11,503 ft.

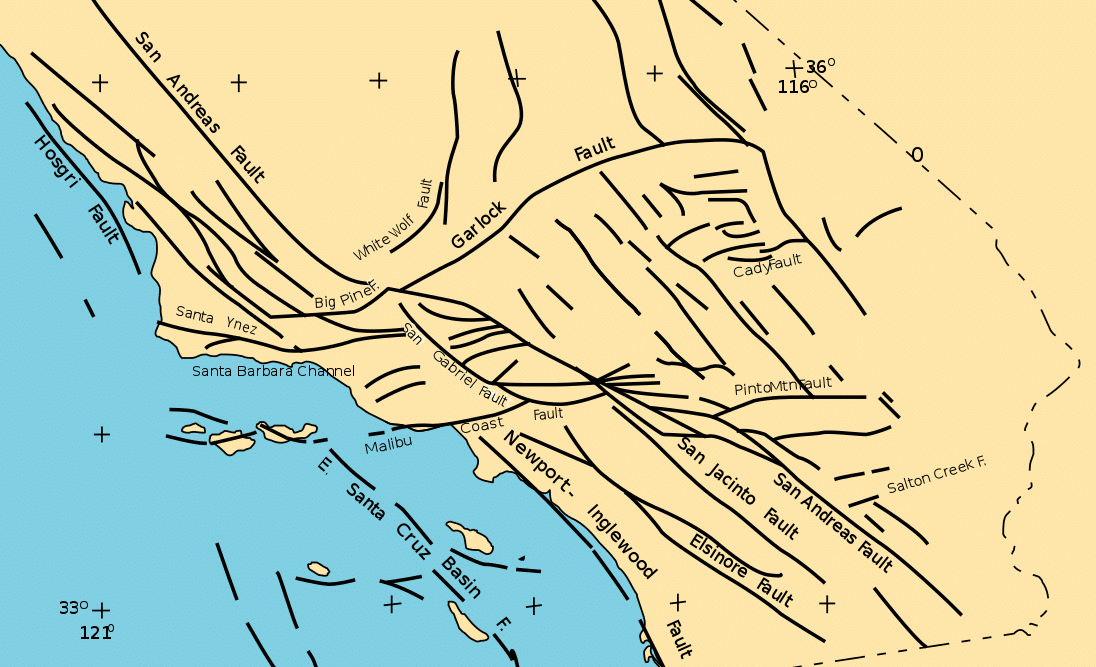

I never saw the bear that day, but as I grew to learn more about the mountains around Los Angeles the incident started to make sense. The varied topography of L.A. and the surrounding area is a result of the 100 or so fault lines under its surface. Over millions of years, the force of tectonic plate collisions at these faults uplifted numerous mountain ranges marked by granite outcroppings, alpine forests of red cedar and lodgepole pines, and some of the most prominent peaks in the contiguous US.

A simplified map Southern California’s fault lines

Steep terrain has mostly protected these areas from urban expansion, resulting in a unique juxtaposition of western wilderness and metropolitan life. Today, only a small population of black bears call these wild places home. But it wasn’t always that way.

What happened to the Grizzly Bears in California?

It may be hard to imagine, but Grizzly bears once roamed freely throughout most of California including Los Angeles county. In fact, there were actually no black bears in L.A. before human habitation, likely because their larger cousins outcompeted them. As was the case in the rest of the state, overhunting and human expansion quickly took a toll on the native Los Angeles Grizzlies and their populations dwindled throughout the late 1800s. By 1916, the last bear in the county had been shot and killed. Fortunately, in 1933, a few wise folks at the California Department of Fish and Wildlife began black bear introduction efforts. These proved successful, and a new population of black bears gained a foothold in the ranges.

A robust Grizzly population might never return to Southern California (at least not without massive investments and public support), but it’s interesting to see just how successful black bears have been at taking over the vacant apex predator position. Today, the black bear population in the Angeles National Forest has increased from that small group of introduced bears to as many as 500 individuals.

What can we do to prevent human-bear conflict in Los Angeles?

Keeping LA bears wild will be an enormous challenge. The amount of edible waste discarded in dumpsters near bear habitat will surely prove too tempting for any hungry black bear to ignore. Bears that consistently seek out human food are often euthanized by land management authorities. In order to protect bears and the ecological services they provide (bears are seed-spreading machines!), we must have a plan for bear-resistant food storage, especially in bear habitat.

A bear encounter in the Angeles National Forest

Campers and backpackers in the Los Angeles backcountry need to properly secure food in order to prevent a much larger problem. One story sent to us from a BearVault user named Leah illustrates this point well:

“I was camping at Henninger Flats just north of Altadena, California. This is not a good place to camp, I later learned, because people who camp at the edge of the city do not store their food safely. I heard other people far away scaring a black bear away from their camp several times throughout the night, and actually walked the 5-10 minutes over to them only to learn that they did not store their food correctly. It was sad for the bear, and I was very glad that the bear would be safe from my food in the canister. Later in the night, I heard the bear walk around my camp, and then to my canister (about 50 yards away?) and it spent about 20 minutes going after my BearVault.

I heard it throwing around the canister and grunting but of course the bear didn’t make it in and finally left (back to the other camp). I let the bear do this because I trusted the BearVault, and otherwise the bear would keep coming back to me. Anyway, in the morning, I found a very scratched up bear canister that had been thrown in coyote poop (gross), and a dent in the shape of a bear claw…”

Leah’s BV500 after getting munched by a bear. All animal damage is covered by our warranty 🙂

Food storage matters

Leah’s story provides an example of how proper food storage techniques (like using a BearVault) can stop bears from getting to human food. Unfortunately, this bear was still able to access food from an unprepared group of campers, further habituating the bear and putting it in serious danger.

Whether they like it or not, folks recreating in the backcountry are on the frontlines of preventing bear-human conflict from getting out of hand. If bears in these backcountry areas never learn to seek out calorically dense human food, odds are they will be less likely to venture into urban areas to forage.

Where do we go from here?

It’s easy to get caught up living in Los Angeles. You could spend a lifetime in the city and never take a second glance at the towering peaks looming on the horizon. As a teenager looking to get out backpacking, blogs like hikingguy.com and the recently defunct but aptly named Nobody Hikes in LA proved invaluable. Once I got a sense of just how many great trails were accessible to me, there was no turning back. It became routine to spend weekends backpacking and hiking. The nearly year-round warm weather and close proximity to trailheads make it shockingly easy to get out.

Angeles National Forest, less than 30 miles from downtown Los Angeles (ignore the dog)

As I spent more time up in the mountains, I started to understand just what an incredible resource they were for folks living in Los Angeles. And I’m not the only one who’s figured that out. While it might be proportionally small in comparison to the population, the SoCal hiking community is alive and growing rapidly. If you don’t believe me, try to find a parking spot at Manker Flats or Icehouse Canyon on a weekend.

These wild areas provide so much to our community, and learning how to safely store food in bear territory is key to ensuring their resilience and longevity. Luckily, it’s pretty easy to do! If you’re camping, have an IGBC certified bear-resistant food storage device like a BearVault. If you’re just heading out for a day hike, maybe think twice before feeding a wild animal some of your granola bar. Not only is it a direct violation of Forest Service Guidelines, it has lasting consequences for the health of the animal and the greater ecosystem.

Bears in Sierra Madre, Burbank, and other foothills communities.

If your neighborhood is dealing with an increase in bears, it’s probably wise to be proactive about food storage. It might just take a few bear-resistant dumpsters to prevent the problem from getting out of hand. Additionally, think about removing easy sources of food like bird feeders and fallen fruit from trees. If you do end up seeing a bear, you can report it to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife here.

The LA Basin from the top of Cucamonga Peak

Author Profile

Kiefer Martin

Kiefer works as the Creative Design Coordinator at BearVault. When he’s not working, he’s usually looking at maps or going to places he saw on maps.