More often than not backpackers and bikepackers consider themselves to be conservationists in one capacity or another. We often support small cottage companies that emphasize quality sustainable materials and of course follow Leave No Trace Principles. However, it seems that when it comes to food and water storage this goes out the window.

We’re getting better at protecting our food and wildlife by doing things like encouraging bear cans for conservation rather than a last-ditch resort once bear problems have escalated. But have you seen the trash we create with food?

Repackaging food to make it fit in our bear cans better (or just to portion out single servings) ends up using so much plastic! The Smartwater brand of disposable water bottles are the gold standard for ultralight water carrying, but add yet another layer of plastic waste. And sure, we reuse these until they fall apart, which is better than a one-and-done, but isn’t there a better way?

The red Klean Kanteen I carried on the Colorado Trail.

The simple answer is yes. The realistic answer is no. Current options for reusable packaging weigh a lot more than the plastic options being utilized. They also cost substantially more – especially upfront. In addition, they tend to be bulky – compare a Stasher Silicone bag to a Ziploc freezer bag. Now consider the interior volume of a bear canister. You can’t fit nearly as much food stored in silicone bags as you can in plastic bags.

With today’s technology and the increasing number of people trying to go further faster, there is an ever-growing movement towards ultralight backpacking. Ultralight backpacking means only one’s essentials are all that are brought, typically weighing a combined 10lbs or less. For food the goal is to carry as many calories per ounce as possible. Ultralight food is usually in the realm of 1.5-2lb per person per day (including the weight of the packaging). The theory is the lighter the weight you must carry, the less impact it has on your body and the faster and further you can go.

The ultralight movement has resulted in dozens of great gear improvements including large decreases in weight and a lower carbon footprint. This movement has also spurred the growth of cottage companies within the outdoor gear world. However, when it comes to food and water storage it seems like the move towards sustainability is happening a bit slower.

If you’re an avid outdoor enthusiast you’ve probably noticed that with the uptick in people getting out (YAY) there’s also an increase in trash – everywhere. So the first step is to actually follow the Leave No Trace principle of pack it in – pack it out. This means you carry ALL of your trash out – TP included (NOTE: Some places require you to pack out ALL waste. Make sure to check the regulations for whatever park you’re visiting before leaving). But what else can we do?

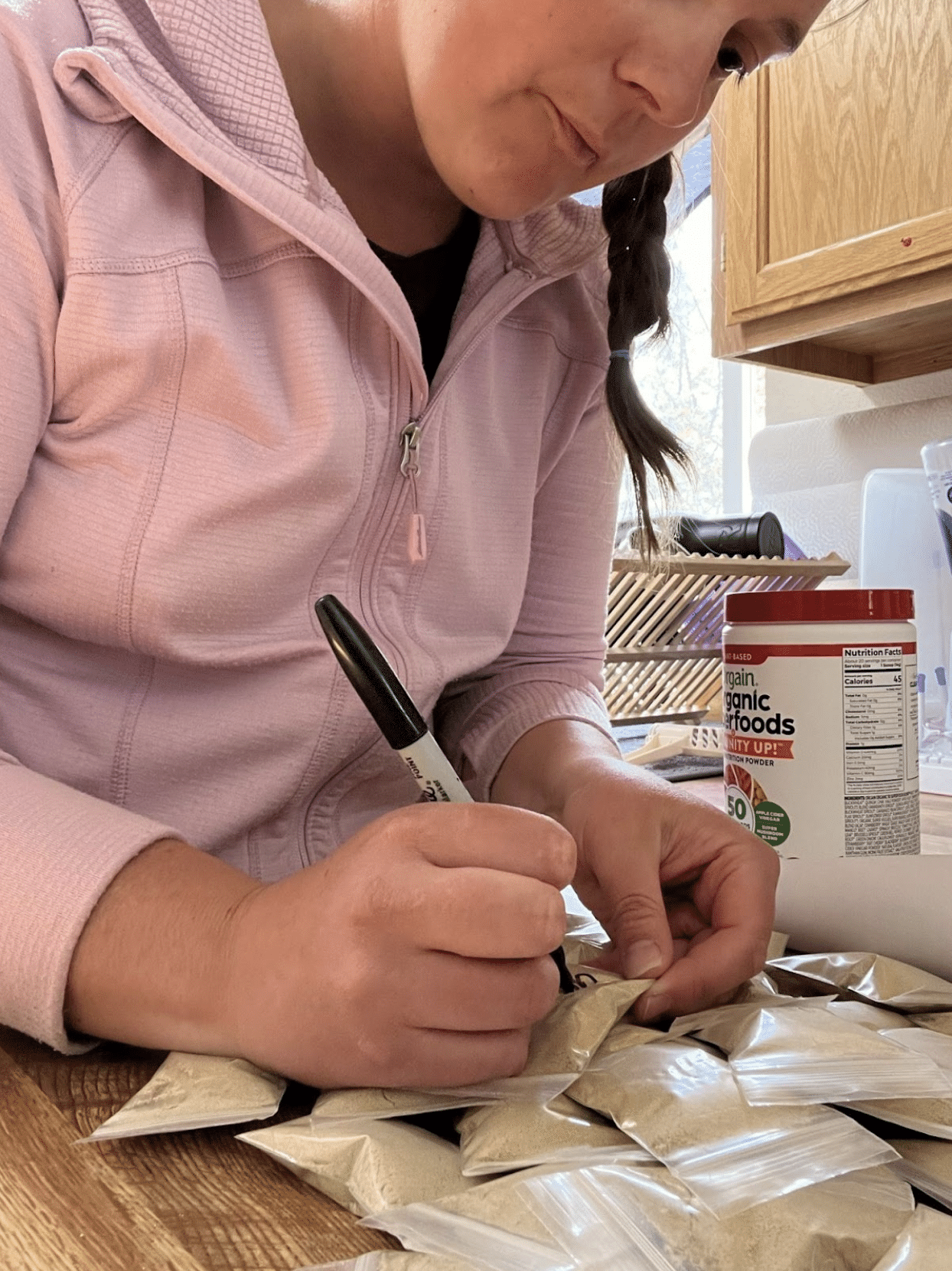

Preparing to fill my BV500. While I don’t repackage pre-packaged food, I am sill a plastic bag user as I haven’t found a better solution that fits. There is clearly a good amount of single serve trash that is made when this is what we eat.

Personally, I will carry a heavier water bottle (usually a Klean Kanteen stainless steel) and soft flasks in place of a Smartwater bottle. These will last me years of hard use, and I’ve had the same water bottle for over 10 years. Yes, it weighs a lot more, but to me it’s worth it and in the end it’s also much cheaper. I like the idea of a titanium water bottle, however most of the ones out there are very very expensive and even heavier than my stainless steel water bottle. I do think this is an area the industry could easily improve. (And it would be nice if the bottles were made to fit in our packs.)

Food is where I struggle. I don’t repackage any pre-packaged food, but a lot of people do because most pre-packaged food is bulky. I also make as much of my own food as I can. When I bulk make food, I store it in mylar bags usually as individual servings. This makes it last pretty much forever, but it doesn’t really solve the trash issue. Mylar can be recycled, but most recycling companies don’t accept it. For short trips, stasher bags work well. But I’m definitely guilty of the freezer bag method, especially for longer trips when I need to fit 10 days of food into a bear can. That means I need to save as much space as possible. To my knowledge there’s no reusable option that saves space like freezer bags.

Some people would bring 1 single large bag with all their oatmeal for a trip instead of 10 individual bags. This does save trash but causes other complications such as portioning struggles, the need for an extra dish, and if that bag rips you typically don’t have another to pull out of your trash.

I do know there are a handful of brands that produce compostable plastic bags. They aren’t super easy to get as of yet, and they won’t compost correctly if just thrown away, as they often are. They also don’t hold up to adding boiling water straight to the bag, which defeats the point of the freezer bag method for most people. And of course they are more expensive. I know a few hikers who wrap meats and hard cheeses in beeswax paper with success. Keep in mind that this won’t work for everything but it’s an idea that can help.

There was no way the plastic jar of greens would fit in my bear can; I individually packaged each day of greens for my thru-hike. I used the smallest plastic bags I could find which helps, but this is still a lot of waste.

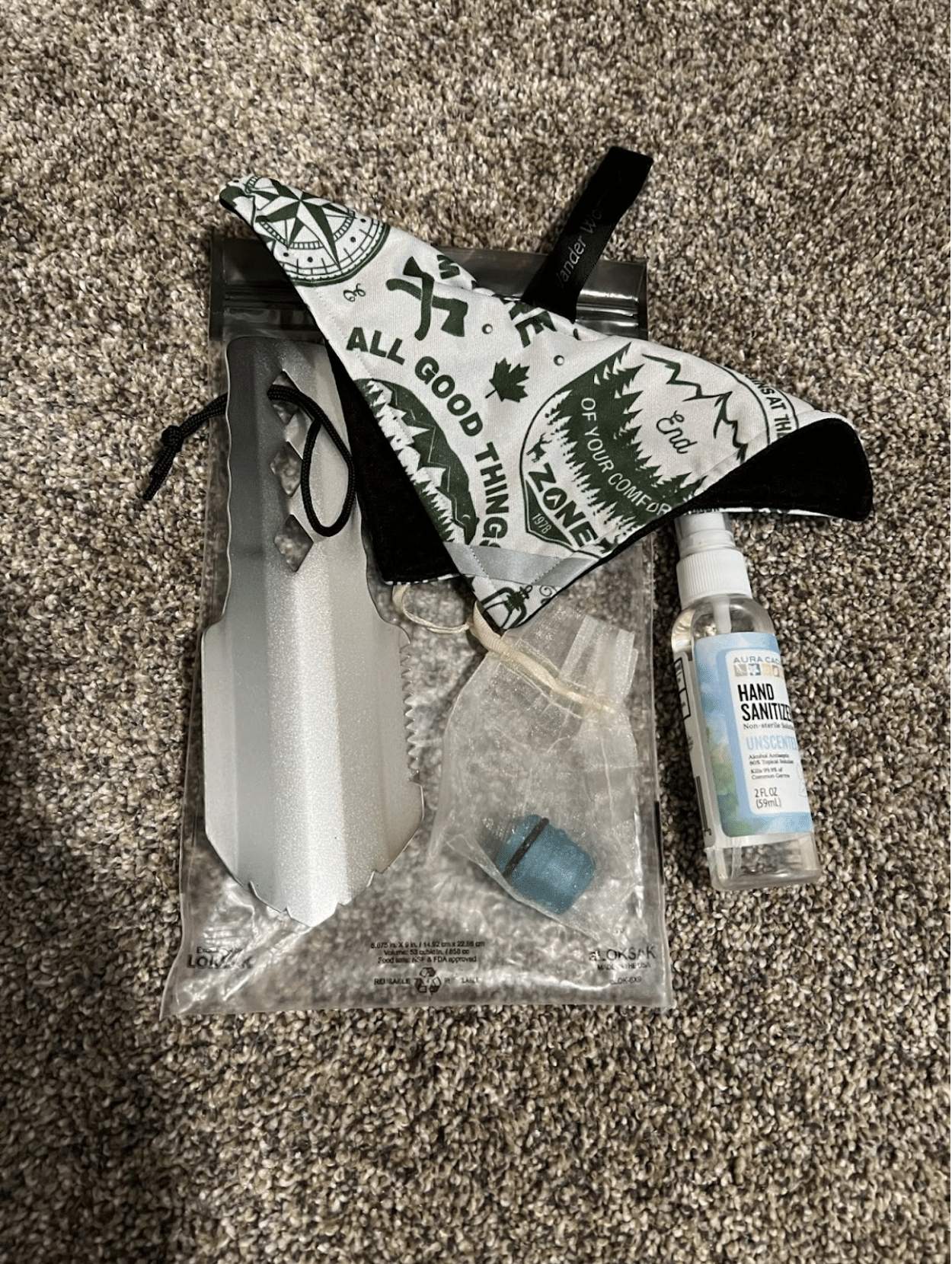

The highest waste producing area of hiking besides food wrapping is food waste followed closely by toilet paper. Toilet paper is probably the easiest to solve and the products exist. I highly recommend you look into joining the club of using a bidet and pee rag (such as a Kula Cloth or Wander Woman Wipe). This method is also fully transferable to daily life and can be used at home and traveling. This eliminates toilet paper completely and often leaves you cleaner than toilet paper would anyways.

Food waste is a bit harder to address as an individual. When you hike long hard days, especially at altitude, a lot of people lose their appetite. This often leads to people not finishing their food and throwing it away. The solution is rather simple, but we need companies who make pre-packaged food to get on board. Making smaller portions of food to cook at a time leads to less food waste because you don’t have to throw away what you can’t eat (because you haven’t cooked it yet).

My toilet kit: Trowel, bidet topper for a water bottle, Wander Woman Wipe, unscented hand sanitizer, small LokSak (recycled package from my socks).

If you make your own food for backpacking this is pretty easy to address. For example, I know I don’t eat much in the morning when I backpack, so I make my oatmeal servings for 1/3 of what the recipe calls for. It took some trial and error to find my sweet spot, but at least now I’m not tossing 2/3 of my breakfast every day. I realize though most people just buy pre-packaged food, which means the only way to address this either causes a lot more plastic waste or requires the companies to change things drastically. One good option is to purchase freeze-dried meals in bulk and portion them yourself.

Cooking dinner in Guadalupe Mountains National Park. My same red Klean Kanteen made it on several national park trips as well. This national park required food be stored in a locked vehicle while in the frontcountry.

There’s also the issue of fuel cans. For years these canisters have been considered non-recyclable. Some recycling places will accept them IF they have been punctured (this allows any remaining fuel to off gas – reducing fire risk). However, many recycling places still will not accept them. I personally refill my canisters as much as possible. This is technically not recommended but with some careful attention to detail many people do successfully refill their cans. This makes for less waste and also saves you some money. A small canister typically survives 8-12 refills in my experience. Always check your threading of the canister as it’s often the first spot to fail. Also don’t fill your canister with the wrong type of fuel (i.e. don’t put propane in an isobutane can).

Overall, there are small things we can do as individuals, but the larger problem resides in how companies deal with the large amount of waste they produce. It’s up to us to demand better sustainability practices from the companies responsible for these wasteful practices.